Fourth Generation – The Forresters of Richmond

“America is another name for opportunity”

-Ralph Waldo Emerson

Narcissa Forrester

Because of the suppressive free black and mulatto laws instituted in Virginia, particularly after the violent, 1831 Nat Turner rebellion, Gustavus sends his young son with his mother Nelly North to be educated and safely cared for. Nelly and Richard return to Richmond around 1836 and are living with Slowey and Catherine Hays. By 1840 Richard and Narcissa the two mixed race offspring of Gustavus Myers and Judah Touro with free women of color marry in Richmond. Quite possibly an arranged marriage, Richard and Narcissa had several children by 1850. Under the Commonwealth of Virginia law at the time, free Negros and persons of color could not remain in the state for more than one year. In order to keep the family together, Catherine, Slowey and Excy Gill listed the Forrester children as their servants and Nelly Forrester was listed with Catherine, Harriet and Julia Myers, the daughters of Moses and Sally Myers. Both sets of families lived together in a large and opulent double house built by Samuel Myers on Broad Street, next to the historic Monumental Church.

In 1854, Catherine Hays passed away in Richmond. Less than three weeks later, Judah Touro died in New Orleans. Neither one knew of the others illness. Both were buried next to each other in the Hebrew Cemetery in Newport, Rhode Island. In her will, Catherine, like her sister Slowey before her, left a sizable bequest to the Forrester family. The following year, Excy Gill died and left her entire estate to the Forrester’s, with the exception of one hundred dollars left to her niece and nephew in Boston. Gustavus Myers acted as executor to all these wills.

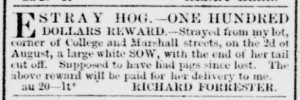

Richmond Times Dispatch 1864

In 1860, Richard and Narcissa are living and thriving in Richmond as free persons of color. Because of an unusual Virginia law created at that time that allowed a handful persons of color to be specially categorized as “free, non-Negro or mulatto,” they were able to live with relative equality with white Richmond citizens. Richard and Narcissa wasted little time starting a family. By 1860, the couple had the first ten of twenty children, and was living in the home Excy Gill willed to them. Many of the children were named after Jewish family members, including, Sarah, Catherine, Julia, Eliza, and Eleazor.

As a free family of color in Richmond, they were afforded access to employment and social life that was mostly unheard of in the years preceding the Civil War. Richard became a successful dairy farmer, contractor and gardener. The Forrester’s lived in their own home at the corner of College and Marshall Streets, across the street from the Virginia Medical College and one block behind the soon-to-be Confederate White House and home of President Jefferson Davis.

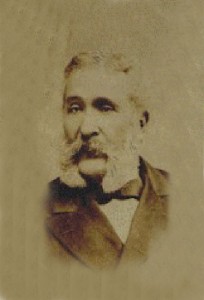

Richard Gustavus Forrester

In 1869, during Southern Reconstruction, and directly following his father Gustavus’ footsteps, Richard Gustavus Forrester became one the first persons of color elected to the city council in Richmond, serving for eleven years. Later, he became the first person of color appointed to the Richmond School Board, which reportedly caused great discord in Post-Reconstruction Richmond. As a school board member, Forrester helped to establish public schools for blacks and the hiring of black teachers and principals. He was also an active member of the American Colonization Society, the Colored Union Labor League and Colored Masons. One Masonic order was organized as the ‘Forrester Lodge.’ Forrester continued his business as a dairy farmer and contractor while serving in public office, and by the time of his death had forty-nine grandchildren, all of whom he had established savings accounts for in the Federal Freedmen’s Bank and later the St. Luke’s Bank. As his father Gustavus had for so many years before, Richard became a political and social leader, but this time for all Richmond citizens both black and white. He died in 1891 and his obituary boasted like his father before him that, “He was one of the most useful colored men of the city.”